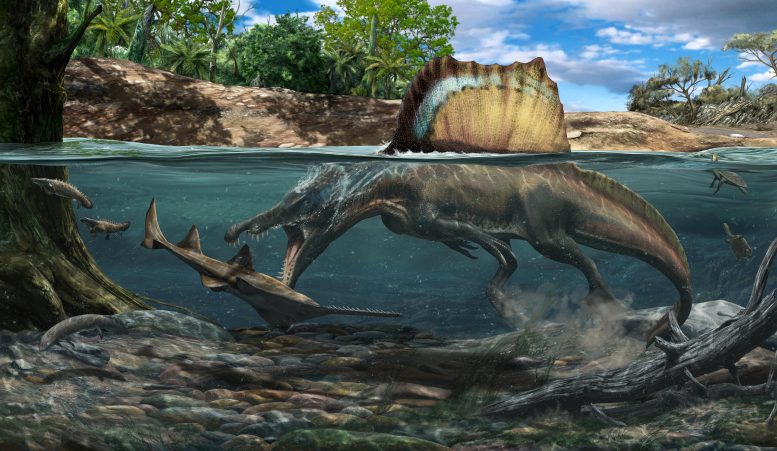

Spinosaurus, el dinosaurio depredador conocido más largo, abre sus mandíbulas alargadas, tachonadas de dientes cónicos, para atrapar la sierra. Contrariamente a las sugerencias anteriores, este animal no se parecía a una garza zancuda: era una «bestia de río», que perseguía activamente a sus presas en un vasto sistema fluvial ubicado en el norte de África moderno. Los huesos densos en el esqueleto del Spinosaurus sugieren fuertemente que pasó mucho tiempo sumergido en el agua. Crédito: David Bonadona

Su primo cercano, Baryonyx, también pudo haber nadado, pero Suchomimus pudo haber vadeado como una garza.

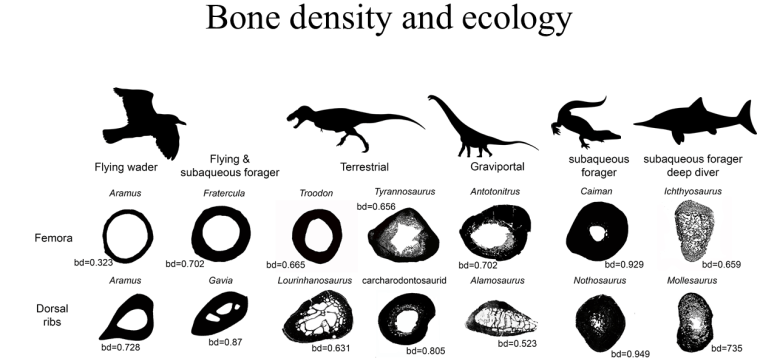

espinosaurio Es el dinosaurio carnívoro más grande jamás descubierto – más grande que Tirano saurio Rex—Pero el método para atraparlos ha sido objeto de debate durante décadas. Es difícil adivinar el comportamiento de un animal que conocemos sólo por los fósiles; Con base en su esqueleto, algunos estudiosos han sugerido que espinosaurio Puede nadar, pero otros piensan que vadea el agua como una garza. Como mirar la anatomía del Spinosaurus no fue suficiente para resolver el misterio, un grupo de paleontólogos está publicando un nuevo estudio en naturaleza Adopta un enfoque diferente: comprobar su densidad ósea. Al analizar la densidad ósea de los espinosaurios y compararlos con otros animales como pingüinos, hipopótamos y cocodrilos, el equipo descubrió que espinosaurio y sus parientes barionix Tenían huesos densos que probablemente les permitieron sumergirse bajo el agua para cazar. Mientras tanto, otro dinosaurio relacionado llamado Schomemus Sus huesos eran más livianos, lo que habría hecho que nadar fuera más difícil, por lo que probablemente vadeará o pasará más tiempo en tierra como otros dinosaurios.

Baryonyx, de Surrey, Inglaterra, nada a través de un antiguo río con un pez en la mandíbula. Al igual que su pariente africano más grande, el Spinosaurus, Baryonyx tenía huesos densos, lo que indica que también pasaba gran parte de su tiempo sumergido en el agua. Anteriormente se pensaba que era menos acuático que su pariente del desierto. Crédito: David Bonadona

dice Matteo Fabri, investigador postdoctoral en el Field Museum y autor principal del libro de estudio naturaleza. «Otros estudios se han centrado en la interpretación de la anatomía, pero está claro que si hay interpretaciones opuestas con respecto a los mismos huesos, esto ya es una clara indicación de que probablemente no sean nuestros mejores indicadores para inferir la ecología de los animales extintos».

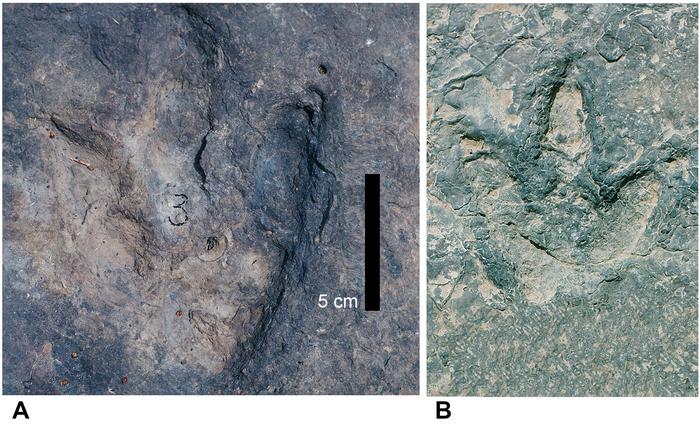

Toda la vida provino inicialmente del agua, y la mayoría de los grupos de vertebrados terrestres tienen órganos posteriores; por ejemplo, mientras que la mayoría de los mamíferos viven en la tierra, tenemos ballenas y focas que viven en el océano, y otros mamíferos como nutrias, tapires y semi- hipopótamos acuáticos. Las aves tienen pingüinos y cormoranes. Los reptiles incluyen cocodrilos, cocodrilos, iguanas marinas y serpientes marinas. Durante mucho tiempo, los dinosaurios no aviares (dinosaurios que no se ramificaron en aves) fueron el único grupo que no tenía habitantes acuáticos. Eso cambió en 2014, cuando un archivo espinosaurio El esqueleto descrito por Nizar Ibrahim en[{» attribute=»»>University of Portsmouth.

Scientists already knew that spinosaurids spent some time by water—their long, croc-like jaws and cone-shaped teeth are similar to other aquatic predators’, and some fossils had been found with bellies full of fish. But the new Spinosaurus specimen described in 2014 had retracted nostrils, short hind legs, paddle-like feet, and a fin-like tail: all signs that pointed to an aquatic lifestyle. But researchers have continued to debate whether spinosaurids actually swam for their food or if they just stood in the shallows and dipped their heads in to snap up prey. This continued back-and-forth led Fabbri and his colleagues to try to find another way to solve the problem.

“The idea for our study was, okay, clearly we can interpret the fossil data in different ways. But what about the general physical laws?” says Fabbri. “There are certain laws that are applicable to any organism on this planet. One of these laws regards density and the capability of submerging into water.”

Simone Maganuco (middle), Davide Bonadonna (right) and lead author Matteo Fabbri (left) organizing fossils at night. Credit: Nanni Fontana

Across the animal kingdom, bone density is a tell in terms of whether that animal is able to sink beneath the surface and swim. “Previous studies have shown that mammals adapted to water have dense, compact bone in their postcranial skeletons,” says Fabbri. Dense bone works as buoyancy control and allows the animal to submerge itself.

“We thought, okay, maybe this is the proxy we can use to determine if spinosaurids were actually aquatic,” says Fabbri.

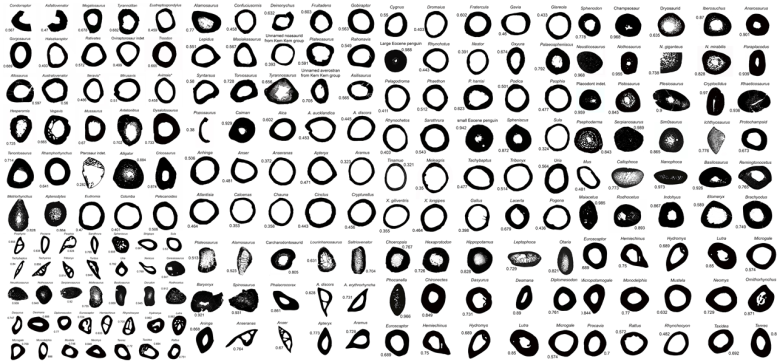

Fabbri and his colleagues, including co-corresponding authors Guillermo Navalón at Cambridge University and Roger Benson at Oxford University, put together a dataset of femur and rib bone cross-sections from 250 species of extinct and living animals, both land-dwellers and water-dwellers. The researchers compared these cross-sections to cross-sections of bone from Spinosaurus and its relatives Baryonyx and Suchomimus. “We had to divide this study into successive steps,” says Fabbri. “The first one was to understand if there is actually a universal correlation between bone density and ecology. And the second one was to infer ecological adaptations in extinct taxa” Essentially, the team had to show a proof of concept among animals that are still alive that we know for sure are aquatic or not, and then applied them to extinct animals that we can’t observe.

When selecting animals to include in the study, the researchers cast a wide net. “We were looking for extreme diversity,” says Fabbri. “We included seals, whales, elephants, mice, hummingbirds. We have dinosaurs of different sizes, extinct marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. We have animals that weigh several tons, and animals that are just a few grams. The spread is very big.”

This menagerie of animals revealed a clear link between bone density and aquatic foraging behavior: animals that submerge themselves underwater to find food have bones that are almost completely solid throughout, whereas cross-sections of land-dwellers’ bones look more like donuts, with hollow centers. “There is a very strong correlation, and the best explanatory model that we found was in the correlation between bone density and sub-aqueous foraging. This means that all the animals that have the behavior where they are fully submerged have these dense bones, and that was the great news,” says Fabbri.

When the researchers applied spinosaurid dinosaur bones to this paradigm, they found that Spinosaurus and Baryonyx both had the sort of dense bone associated with full submersion. Meanwhile, the closely related Suchomimus had hollower bones. It still lived by water and ate fish, as evidenced by its crocodile-mimic snout and conical teeth, but based on its bone density, it wasn’t actually swimming.

Other dinosaurs, like the giant long-necked sauropods also had dense bones, but the researchers don’t think that meant they were swimming. “Very heavy animals like elephants and rhinos, and like the sauropod dinosaurs, have very dense limb bones, because there’s so much stress on the limbs,” explains Fabbri. “That being said, the other bones are pretty lightweight. That’s why it was important for us to look at a variety of bones from each of the animals in the study.” And while there are limitations to this kind of analysis, Fabbri is excited by the potential for this study to tell us about how dinosaurs lived.

“One of the big surprises from this study was how rare underwater foraging was for dinosaurs, and that even among spinosaurids, their behavior was much more diverse that we’d thought,” says Fabbri.

Jingmai O’Connor, a curator at the Field Museum and co-author of this study, says that collaborative studies like this one that draw from hundreds of specimens, are “the future of paleontology. They’re very time-consuming to do, but they let scientists shed light onto big patterns, rather than making qualitative observations based on one fossil. It’s really awesome that Matteo was able to pull this together, and it requires a lot of patience.”

Fabbri also notes that the study shows how much information can be gleaned from incomplete specimens. “The good news with this study is that now we can move on from the paradigm where you need to know as much as you can about the anatomy of a dinosaur to know about its ecology, because we show that there are other reliable proxies that you can use. If you have a new species of dinosaur and you just have only a few bones of it, you can create a dataset to calculate bone density, and at least you can infer if it was aquatic or not.”

Reference: “Subaqueous foraging among carnivorous dinosaurs” by Matteo Fabbri, Guillermo Navalón, Roger B. J. Benson, Diego Pol, Jingmai O’Connor, Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, Gregory M. Erickson, Mark A. Norell, Andrew Orkney, Matthew C. Lamanna, Samir Zouhri, Justine Becker, Amanda Emke, Cristiano Dal Sasso, Gabriele Bindellini, Simone Maganuco, Marco Auditore and Nizar Ibrahim, 23 March 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04528-0

«Erudito en viajes incurable. Pensador. Nerd zombi certificado. Pionero de la televisión extrema. Explorador general. Webaholic».