Investigadores de la Escuela de Medicina de la Universidad de Washington en St. Louis han descubierto que vacunar ratones contra la toxina puede prevenir el daño a los intestinos, un descubrimiento que apunta a nuevas formas de prevenir la desnutrición y el retraso del crecimiento en los niños.

Se ha demostrado que la vacunación en ratones previene el daño intestinal causado por las toxinas producidas por bacterias que causan diarrea.

La diarrea era una de las principales causas de muerte entre los niños menores de cinco años a mediados del siglo XX y mataba a unos 4,5 millones de niños al año. Aunque la terapia de rehidratación oral redujo significativamente la mortalidad, no previno la infección. Millones de niños en países de ingresos bajos y medianos aún sufren episodios frecuentes de diarrea, lo que debilita sus cuerpos y los hace vulnerables a la desnutrición y al retraso en el crecimiento, así como a otras infecciones.

investigadores en Escuela de Medicina de la Universidad de Washington en St. Louis ¿Cómo averiguó qué causa la diarrea? coli La bacteria daña el intestino, lo que provoca desnutrición y retraso en el crecimiento. Mediante estudios en células humanas y ratones, también han demostrado que la vacunación contra la toxina producida por estos coli Los ratones pueden proteger a los bebés del daño intestinal.

Los resultados indican que se dispone de una vacuna contra este tipo coli Puede promover los esfuerzos globales para garantizar que todos los niños no solo lleguen a la edad de cinco años, sino que también prosperen. El estudio fue publicado recientemente en la revista

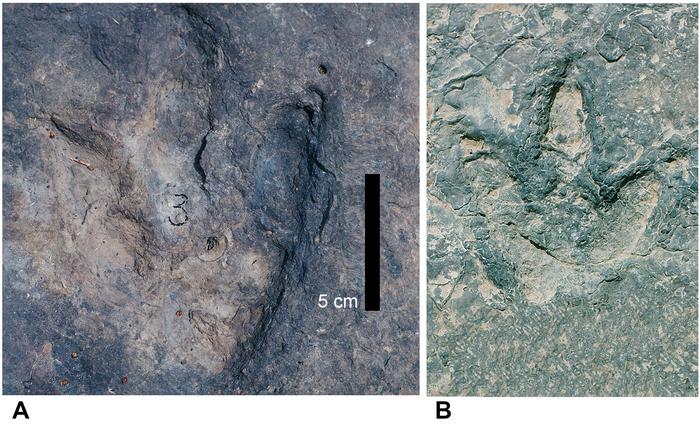

The lining of a healthy intestine features tightly packed projections called microvilli that absorb nutrients (left), but exposure to a bacterial toxin damages the microvilli (right) and impairs nutrient absorption. Credit: Alaullah Sheikh/Washington University

“Ideally, we’d like to have a vaccine that prevents acute diarrhea, which still kills half a million children a year, and that also protects against long-term effects such as malnutrition, which is perhaps the bigger part of the problem now,” said senior author James M. Fleckenstein, MD, a professor of medicine and of molecular microbiology. “When kids become malnourished, their risk of dying from any cause goes up. The World Health Organization is in the process of deciding how to prioritize vaccines for kids in low- and middle-income countries, and I think these data suggest that vaccinating kids against E. coli diarrhea could be hugely beneficial in places that struggle with this.”

Fleckenstein studies a kind of E. coli known as enterotoxigenic E. coli, or ETEC — so named for the two toxins it produces — and its effects on children who live where the bacteria run rampant. E. coli is a common cause of diarrhea worldwide, but the strains found in the U.S. and other high-income countries typically don’t carry the same toxins as those in low- and middle-income countries. And that may make all the difference.

A 2020 study by Fleckenstein and Alaullah Sheikh, Ph.D. — then a postdoctoral researcher in Fleckenstein’s lab and now an instructor in medicine — indicated that one of ETEC’s two toxins, heat-labile toxin, does more than trigger a case of the runs. The toxin also affects gene expression in the gut, ramping up genes that help the bacteria stick to the gut wall.

As part of the latest study, Fleckenstein and Sheikh discovered that the toxin suppresses a whole suite of genes related to the lining of the intestines, where nutrients are absorbed. The so-called brush border of the intestine is composed of microscopic, finger-like projections called microvilli that are tightly packed over the surface of the intestines like bristles on a brush. When Fleckenstein and Sheikh applied the toxin to clusters of human intestinal cells, the brush border disintegrated.

“Instead of being nice and tight and upright with thousands of microvilli per cell, they are short, floppy and sparse, kind of like if you had plucked out most of the bristles, and what was left was kind of raggedy,” said Sheikh, who led the 2020 and current studies. “That alone would have a negative impact on the body’s ability to absorb nutrients. But on top of that, we found that genes related to absorbing specific vitamins and minerals — notably vitamin B1 and zinc — also were downregulated. That could explain some of the micronutrient deficiencies we see in children repeatedly exposed to these bacteria.”

Children in low- and middle-income countries tend to get diarrhea over and over, and the risk of malnutrition and stunting goes up with each bout. Studying infant mice, the researchers found that a single infection with toxin-producing E. coli was sufficient to damage the brush border, while repeated infections led to extensive intestinal damage and growth lag. Pups infected with a strain of E. coli that lacks the toxin showed no such intestinal damage or stunting.

If the toxin is the problem, an immune response neutralizing the toxin may prevent the long-term effects, Fleckenstein and Sheikh reasoned. To find out, they vaccinated nursing mouse mothers with the toxin. Suckling mice are too young to be immunized themselves, but their vaccinated mothers produce antibodies that pass to the pups through breast milk. The researchers found that the intestines of infant mice from vaccinated mothers appeared healthy, suggesting that vaccination can protect against intestinal damage leading to malnutrition.

“This is an argument for developing a vaccine for this kind of E. coli,” Fleckenstein said. “There are lifelong consequences of getting infected over and over in childhood. Vaccination combined with efforts to improve sanitation and access to clean water could protect children from the long-term effects and give them a better shot at long and healthy lives.”

Reference: “Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin drives enteropathic changes in small intestinal epithelia” by Alaullah Sheikh, Brunda Tumala, Tim J. Vickers, John C. Martin, Bruce A. Rosa, Subrata Sabui, Supratim Basu, Rita D. Simoes, Makedonka Mitreva, Chad Storer, Erik Tyksen, Richard D. Head, Wandy Beatty, Hamid M. Said and James M. Fleckenstein, 12 November 2022, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-34687-7

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, and the National Institutes of Health.

«Erudito en viajes incurable. Pensador. Nerd zombi certificado. Pionero de la televisión extrema. Explorador general. Webaholic».